How do you bridge a gap created by a language barrier, by differing cultural norms and expectations for childcare, by a system without the capacity needed for family demand and lacking at times in resources for Spanish-speaking providers? For 6 dedicated women working in Lexington, Nebraska, the answer may come in small acts of trust.

Patti Mahrt Roberts of Roberts Early Childhood Consulting describes the situation under which four Spanish-speaking early childhood professionals joined with Patti and interpreter Maria Salas to undertake Pyramid Model Training. Roberts explains, “these providers have to be very careful with money.” In fact, one of the women who joined training had been using three safe but broken cots because she had to make do. As part of the training, the four providers received small stipends, often as checks of about $25. When the women cashed these checks at local banks and stores, they were charged fees of sometimes half the amount or more. How then can they trust the system?

When Preschool Development Grant funds became available to provide coaching and training to these four providers, Roberts and Salas teamed up to start the process of connecting. In the beginning, Salas said the providers were reluctant. “Some didn’t want to join, didn’t know what to expect,” she said. She goes on to add, “we were strangers coming into their homes.” Roberts, too, said there was “definite mistrust in the beginning.”

But Roberts and Salas persevered, determined to build the necessary trust to partner with these educators. Roberts brought the Pyramid Model know-how, but lacked the language skills and lived cultural experience to translate training. Salas had lived in the area for nearly 30 years and had worked as an interpreter with the public school system for 20 of those years. She then could not only translate training into Spanish, but also interpret and rework concepts that did not culturally convert.

Roberts described the model of childcare as based more in caretaking before training began. She said the children were well fed, kept safe, and in one particular instance, had a lovely hair care period with the provider. They didn’t, however, have a schedule of activities designed to prepare children developmentally. In fact, Roberts said schedule building was one of the most difficult parts of training.

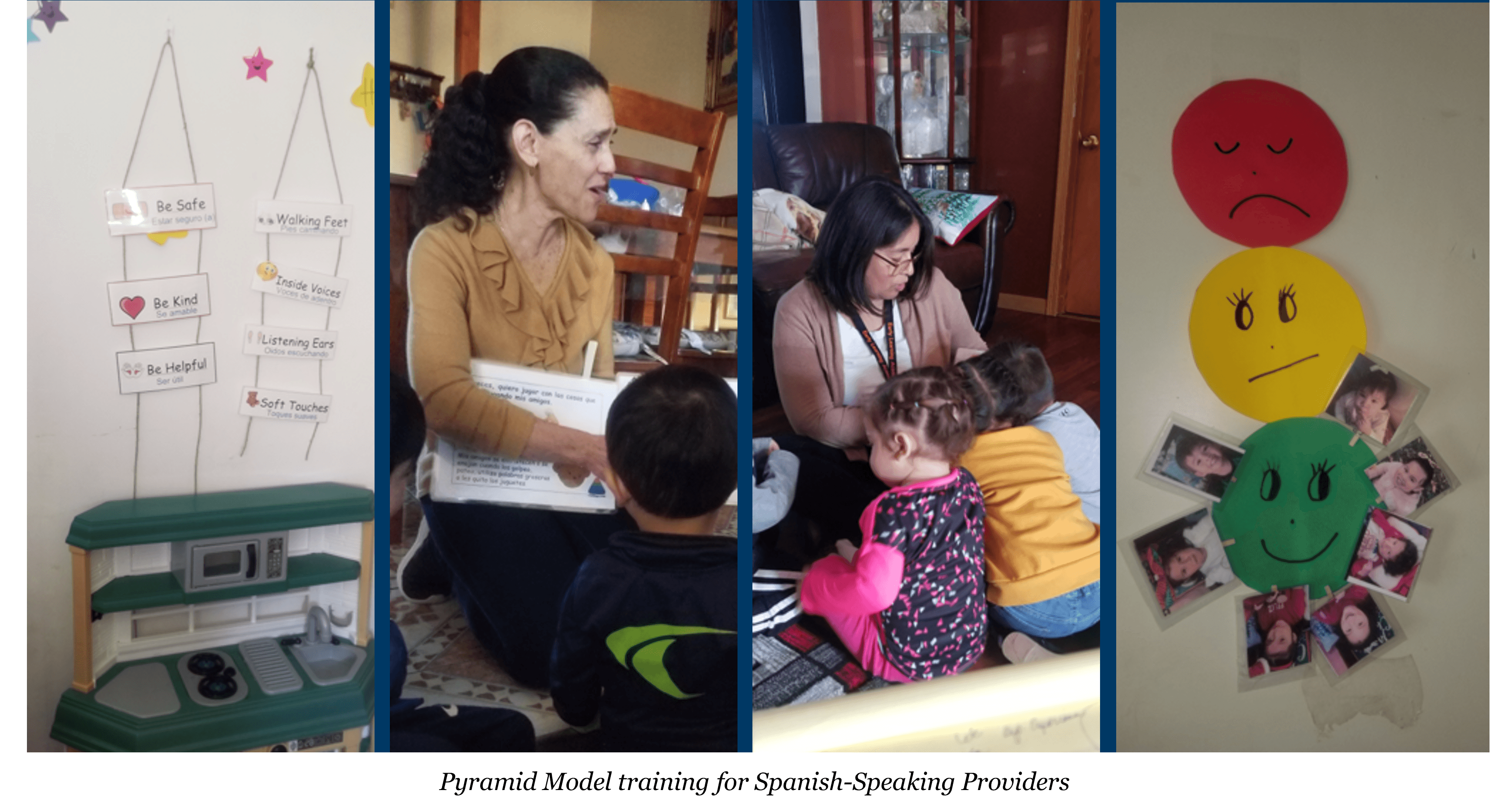

Training began with the four providers, who ranged from comprehending English but speaking very little to almost solely Spanish-speaking, by allowing Roberts to work with the children to demonstrate skills while the providers watched. She said that the women wanted to see it modeled because they wanted to be sure they were implementing techniques correctly. Some sessions were more difficult, such as schedule building and creating rules and expectations that the children would follow. At times, Salas had to rethink situations and metaphors that were more culturally appropriate to keep training moving forward. Other sessions were favorites. Roberts said of the “teaching kids emotions” segment that “They (the providers) took it and ran with it.” She describes an innovative exercise in which one woman put emotions in a tissue box and had the children draw from the box. They then had to physically demonstrate the emotion to the other children. Roberts also said that all the providers loved the section on friendship building.

Little by little things began to change and trust began to grow. One provider said that establishing rules and expectations had made her time-out corner almost disappear. Another provider moved from a few toys in labeled drawers to bins of activities and toys that were visible to the children and that engaged them not only in play, but also in the important skill of cleaning up. And training came with funds to equip their facilities. Remember the broken cots? That provider was able to purchase 4 new cots. Another was able to purchase a child size table where she could label the children’s spots. Finally,

Roberts talked to the Rooted in Relationships stakeholder committee about the issue of cashing checks. A stakeholder member volunteered to contact the bank and was able to persuade them to change their policy for the childcare providers' stipend checks. These were the small acts that, with time, patience, and clear demonstration of care for the women and their children, built trust.

Roberts said that it was about 4 months before the group began to trust her, which had a big impact on her. “I was the outsider, but now I’ve been accepted,” she said. “It’s my favorite project.” Providers responses were equally enthusiastic. One woman named Lete said, “I wish we had the training every month.” Salas said another woman said, after the program was complete, “I miss the training.” Indeed, Salas has already heard from one of the women that she has a friend asking when she can get into the program.

At the end of the training, Roberts noted that “these children are so cared for. It’s beautiful.” She adds that “if they get licensed it’ll be even better. They can care for more children and receive more funds.” Salas, who is getting her coaching certification so that she can train on her own, says, “It’s a good program. Childcare providers will benefit from it. And once they know the procedures, they begin to see the children and their care differently.” It’s this kind of trust-building that leads to greater access, to higher quality care, to partnerships with all of Nebraska’s providers and families.